Lyotard found particularly interesting the explanation of the sublime offered by Immanuel Kant in his Critique of Judgment (sometimes Critique of the Power of Judgment). In this book Kant explains this mixture of anxiety and pleasure in the following terms: there are two kinds of 'sublime' experience. In the 'mathematically' sublime, an object strikes the mind in such a way that we find ourselves unable to take it in as a whole. More precisely, we experience a clash between our reason (which tells us that all objects are finite) and the imagination (the aspect of the mind that organises what we see, and which sees an object incalculably larger than ourselves, and feels infinite). In the 'dynamically' sublime, the mind recoils at an object so immeasurably more powerful than we, whose weight, force, scale could crush us without the remotest hope of our being able to resist it. (Kant stresses that if we are inactual danger, our feeling of anxiety is very different from that of a sublime feeling. The sublime is an aesthetic experience, not a practical feeling of personal danger.) This explains the feeling of anxiety.

What is deeply unsettling about mathematical beauty is that the mental faculties that present visual perceptions to the mind are inadequate to the concept corresponding to it; in other words, what we are able to make ourselves see cannot fully match up to what we know is there. We know it's a mountain but we cannot take the whole thing into our perception. Our sensibility is incapable of coping with such sights, but our reason can assert the finitude of the presentation[citation needed]. With the dynamically sublime, our sense of physical danger should prompt an awareness that we are not just physical material beings, but moral and (in Kant's terms) noumenal beings as well. The body may be dwarfed by its power but our reason need not be. This explains, in both cases, why the sublime is an experience of pleasure as well as pain.

Lyotard is fascinated by this admission, from one of the philosophical architects of the Enlightenment, that the mind cannot always organise the world rationally. Some objects are simply incapable of being brought neatly under concepts. For Lyotard, in Lessons on the Analytic of the Sublime, but drawing on his argument in The Differend, this is a good thing. Such generalities as 'concepts' fail to pay proper attention to the particularity of things. What happens in the sublime is a crisis where we realise the inadequacy of the imagination and reason to each other. What we are witnessing, says Lyotard, is actually the differend; the straining of the mind at the edges of itself and at the edges of its conceptuality.

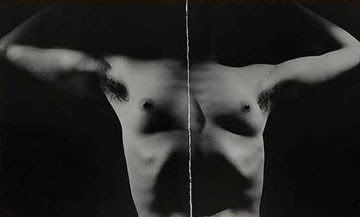

The minotaur by Man Ray

No comments:

Post a Comment